Hyjnitë

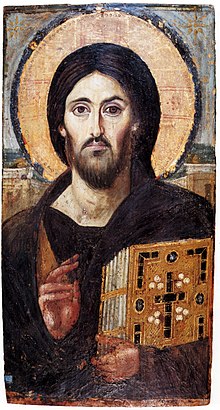

Hyjnitë janë qenie të mbinatyrshme, të cilat konsiderohen hyjnore ose të shenjta.[1] Hyjnitë përshkruhen zakonisht si "perëndi apo perëndeshë (në një fe politeiste)", ose diçka që respektohet si hyjnore.[2] C. Scott Littleton përkufizon një hyjni si "një qenie me fuqi më të madhe se ato të njerëzve të zakonshëm, por që ndërvepron me njerëzit, pozitivisht apo negativisht, në mënyra që i çojnë njerëzit në nivele të reja të vetëdijes, përtej preokupimeve të bazuara të jetës së zakonshme".[3] Në gjuhën shqipe, në rastin e gjinisë mashkullore quhet hyjni, ndërsa në rastin e gjinisë femërore, quhet hyjneshë.

Fetë mund të kategorizohen nga sa hyjnitë ata adhurojnë. Fetë monoteiste pranojnë vetëm një hyjni (kryesisht të referuar si Perëndi),[4][5] fetë politeiste pranojnë hyjnitë e shumta.[6] Fetë henotheiste pranojnë një hyjni supreme pa u mohuar hyjnitë e tjera, duke i konsideruar ato si aspekte të të njëjtit parim hyjnor;[7][8] dhe fetë jo teiste mohojnë çdo hyjni të lartë krijues të përjetshëm, por pranojnë një panteon të hyjnive që jetojnë, vdesin dhe mund të rilinden si çdo qenie tjetër.[9]:35–37[10]:357–358

Megjithëse shumica e feve monoteiste tradicionalisht e parashikojnë Perëndinë e tyre si të gjithëfuqishëm, të gjithëpranishëm, të gjithëdijshëm, të gjithëpranishëm dhe të përjetshëm,[11][12][13] asnjë nga këto cilësi nuk janë thelbësore për përcaktimin e "hyjnisë" politeiste[14][15][16] dhe kulturat e ndryshme konceptuan hyjnitë e tyre ndryshe.[14][15] Fetë monoteiste zakonisht i referohen Perëndisë në terma mashkullor,[17][18]:96 ndërsa fetë e tjera u referohen hyjnive të tyre në mënyra të ndryshme - mashkullore, femërore, androgjene dhe pa gjini.[19][20][21]

Historikisht, shumë kultura të lashta - duke përfshirë mesopotamët e lashtë, egjiptianët e lashtë, grekët e lashtë, romakët, njerëzit e veriut - personifikonin fenomenet natyrore ndryshe si shkaqe apo efekte të qëllimshme.[22][23][24] Disa hyjne Avestane dhe Vedike u konsideruan si koncepte etike.[22][23] Në fetë indiane, hyjnitë u parashikuan si manifestim brenda tempullit të trupit të çdo qenieje të gjallë, si organe shqisore dhe mendje.[25][26][27] Hyjnitë u parashikuan si një formë ekzistence (Sawsar) pas rilindjes, për qeniet njerëzore që fitojnë meritë përmes një jete etike, ku bëhen hyjnitë kujdestare dhe jetojnë me lumturi në qiell, por gjithashtu i nënshtrohen vdekjes kur meritat e tyre janë të humbura.[9]:35–38[10]:356–59

Shiko edhe

RedaktoReferime

Redakto- ^ O'Brien, Jodi (2009). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society (në anglisht). Los Angeles: Sage. fq. 191. ISBN 978-1-4129-0916-7. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English (në anglisht) (bot. 3rd). New York: Oxford University Press. fq. 461. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology (në anglisht). New York: Marshall Cavendish. fq. 378. ISBN 978-0-7614-7559-0. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo; Vriezen, Karel (2001). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah (në anglisht). London: New York. fq. 189. ISBN 978-0-567-23212-0. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

The Christian tradition is, in imitation of Judaism, a monotheistic religion. This implies that believers accept the existence of only one God. Other deities either do not exist, are seen as the product of human imagination or are dismissed as remanents of a persistent paganism

- ^ Korte, Anne-Marie; Haardt, Maaike De (2009). The Boundaries of Monotheism: Interdisciplinary Explorations Into the Foundations of Western Monotheism (në anglisht). Brill. fq. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-17316-3. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Brown, Jeannine K. (2007). Scripture as Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics (në anglisht). Baker Academic. fq. 72. ISBN 978-0-8010-2788-8. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Harrison, Victoria S.; Goetz, Stewart (2012). The Routledge Companion to Theism (në anglisht). Routledge. fq. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-136-33823-6. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Reat, N. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind (në anglisht). Cambridge University Press. fq. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-521-33159-3. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ a b Keown, Damien (2013). Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (në anglisht) (bot. New). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966383-5. Marrë më 22 qershor 2017.

- ^ a b Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism (në anglisht). Oxford University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-19-964465-0. Marrë më 22 qershor 2017.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Marty, Elsa J. (2010). A Dictionary of Philosophy of Religion. A&C Black. fq. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-4411-1197-5.

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ Wilkerson, W.D. (2014). Walking With The Gods. Lulu.com. fq. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-9915300-1-4.

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (bot. 1st). Cambridge University Press. fq. 473–74. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ a b Hood, Robert Earl. Must God Remain Greek?: Afro Cultures and God-talk. Fortress Press. fq. 128–29. ISBN 978-1-4514-1726-5.

African people may describe their deities as strong, but not omnipotent; wise but not omniscient; old but not eternal; great but not omnipresent (...)

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ a b Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (bot. 1st). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. fq. 441–42. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

[Historically...] people perceived far fewer differences between themselves and the gods than the adherents of modern monotheistic religions. Deities were not thought to be omniscient or omnipotent and were rarely believed to be changeless or eternal

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ Murdoch, John (1861). English Translations of Select Tracts, Published in India: With an Introd. Containing Lists of the Tracts in Each Language. Graves. fq. 141–42.

We [monotheists] find by reason and revelation that God is omniscient, omnipotent, most holy, etc, but the Hindu deities possess none of those attributes. It is mentioned in their Shastras that their deities were all vanquished by the Asurs, while they fought in the heavens, and for fear of whom they left their abodes. This plainly shows that they are not omnipotent.

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ Kramarae, Cheris; Spender, Dale (2004). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women's Issues and Knowledge (në anglisht). Routledge. fq. 655. ISBN 978-1-135-96315-6. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ O'Brien, Julia M. (2014). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Gender Studies (në anglisht). Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-19-983699-4. Marrë më 22 qershor 2017.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1992). Roman and European Mythologies (në anglisht). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. fq. 274–75. ISBN 978-0-226-06455-0. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Pintchman, Tracy (2014). Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess (në anglisht). SUNY Press. fq. 1–2, 19–20. ISBN 978-0-7914-9049-5. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Nathaniel (2016). To Be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum (në anglisht). University of California Press. fq. xv. ISBN 978-0-520-96363-4. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ a b Malandra, William W. (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion: Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid Inscriptions (në anglisht). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. fq. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-8166-1115-7. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ a b Fløistad, Guttorm (2010). Volume 10: Philosophy of Religion (në anglisht) (bot. 1st). Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media B.V. fq. 19–20. ISBN 978-90-481-3527-1. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations (bot. st). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. fq. 272–74. ISBN 978-0-8014-3339-9. Marrë më 22 janar 2018.

{{cite book}}: Mungon ose është bosh parametri|language=(Ndihmë!) - ^ Potter, Karl H. (2014). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 3: Advaita Vedanta up to Samkara and His Pupils (në anglisht). Princeton University Press. fq. 272–74. ISBN 978-1-4008-5651-0. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2006). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation (në anglisht). New York: Oxford University Press. fq. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.

- ^ Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism (në anglisht). London: Routledge. fq. 899–900. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2. Marrë më 28 qershor 2017.