Republika gjysmë presidenciale

| |||||

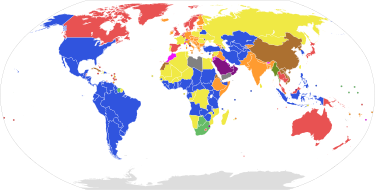

| Sistemet e qeverisjes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Një republikë gjysmë-presidenciale, ose republikë e dyfishtë ekzekutive, është një republikë në të cilën një president ekziston së bashku me një kryeministër dhe një kabinet, ku dy të fundit janë përgjegjës ndaj legjislativit të shtetit. Ai ndryshon nga një republikë parlamentare në atë që ka një kryetar shteti të zgjedhur nga populli; dhe nga sistemi presidencial në atë që kabineti, megjithëse emërohet nga presidenti, është përgjegjës para legjislativit, i cili mund ta detyrojë kabinetin të japë dorëheqjen përmes një mocioni mosbesimi.[1][2][3]

Ndërsa Republika e Weimarit (1919-1933) dhe Finlanda (nga 1919 deri në 2000) ilustronin sistemet e hershme gjysmë-presidenciale, termi "gjysmë-presidencial" u prezantua për herë të parë në 1959 në një artikull nga gazetari Hubert Beuve-Méry, [4] dhe popullarizuar nga një vepër e vitit 1978 e shkruar nga shkencëtari politik Maurice Duverger, [5] që të dy synonin të përshkruanin Republikën e Pestë Franceze (themeluar në 1958). [6][7][8]

Përkufizimi

RedaktoPërkufizimi origjinal i Maurice Duverger për gjysmë-presidencializmin thoshte se presidenti duhej të zgjidhej, të kishte pushtet të konsiderueshëm dhe të shërbente për një mandat të caktuar. [9] Përkufizimet moderne thjesht deklarojnë se kreu i shtetit duhet të zgjidhet dhe se një kryeministër i veçantë që varet nga besimi i parlamentit duhet të udhëheqë ekzekutivin. [9]

Nëntipet

RedaktoEkzistojnë dy nëntipe të dallueshme të gjysmë-presidencializmit: krye-presidencializmi dhe president-parlamentarizmi.

Sipas sistemit kryeministër-presidencial, kryeministri dhe kabineti janë ekskluzivisht përgjegjës para parlamentit. Presidenti mund të zgjedhë kryeministrin dhe kabinetin, por vetëm parlamenti mund t'i miratojë dhe t'i largojë nga detyra me votë mosbesimi. Ky sistem është shumë më afër parlamentarizmit të pastër. Ky nëntip përdoret në: Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, [10] Timorin Lindor, [10] [11] Francë, Lituani, Madagaskar, Mali, Mongoli, Niger, Gjeorgji (2013–2018), Poloni ( de facto, megjithatë, sipas Kushtetutës, Polonia është një republikë parlamentare ),[12][13] Portugalia, Rumania, São Tomé dhe Principe, [10] Sri Lanka, Turqi ( de facto midis 2014–2018, deri në ndryshimin kushtetues të kaloni qeverinë në presidenciale nga parlamentare ) dhe Ukrainën (që nga viti 2014; më parë, midis 2006 dhe 2010). [14]

Sipas sistemit president-parlamentar, kryeministri dhe kabineti janë dyfish përgjegjës para presidentit dhe parlamentit. Presidenti zgjedh kryeministrin dhe kabinetin, por duhet të ketë mbështetjen e shumicës parlamentare për zgjedhjen e tij. Për të hequr një kryeministër, ose të gjithë kabinetin, nga pushteti, presidenti ose mund t'i shkarkojë ata, ose parlamenti mund t'i largojë me një votë mosbesimi . Kjo formë e gjysmë-presidencializmit është shumë më afër presidencializmit të pastër. Përdoret në: Guinea-Bissau, [15] Mozambik, Rusi dhe Tajvan . Ai u përdor gjithashtu në Ukrainë (së pari midis 1996 dhe 2005; më pas nga 2010 në 2014), Gjeorgji (nga 2004 deri në 2013), Koreja e Jugut nën republikën e Katërt dhe të Pestë, dhe në Gjermani gjatë Republikës së Vajmarit.[16]

Bashkëjetesa

RedaktoNë një sistem gjysmë-presidencial, presidenti dhe kryeministri ndonjëherë mund të jenë nga parti të ndryshme politike. Ky quhet " bashkëjetesa ", një term i cili e ka origjinën në Francë pasi situata u krijua për herë të parë në vitet 1980. Bashkëjetesa mund të krijojë ose një sistem efektiv kontrollesh dhe balancash, ose një periudhë gurësh të ashpër dhe të tensionuar, në varësi të qëndrimeve të dy liderëve, ideologjive të tyre/partive të tyre dhe kërkesave të mbështetësve të tyre. [17]

Ndarja e pushteteve

RedaktoShpërndarja e pushtetit midis presidentit dhe kryeministrit mund të ndryshojë shumë midis vendeve.

Në Francë, për shembull, në rastin e bashkëjetesës, presidenti mbikëqyr politikën e jashtme dhe politikën e mbrojtjes (këto quhen përgjithësisht les prérogatives présidentielles, prerogativa presidenciale) dhe kryeministri është përgjegjës për politikën e brendshme dhe politikën ekonomike.[18] Në këtë rast, ndarja e përgjegjësive ndërmjet kryeministrit dhe presidentit nuk është shprehur shprehimisht në kushtetutë, por ka evoluar si një konventë politike bazuar në parimin kushtetues që kryeministri emërohet (me miratimin e mëvonshëm të shumicës parlamentare. ) dhe shkarkohet nga presidenti. [19] Nga ana tjetër, sa herë që presidenti dhe kryeministri përfaqësojnë të njëjtën parti politike, e cila drejton kabinetin, ata tentojnë të ushtrojnë kontroll de facto mbi të gjitha fushat e politikës nëpërmjet kryeministrit. Megjithatë, i takon presidentit të vendosë se sa autonomi i mbetet kryeministrit të përmendur.

Në shumicën e rasteve, bashkëjetesa rezulton nga një sistem në të cilin dy drejtuesit nuk zgjidhen në të njëjtën kohë ose për të njëjtin mandat. Për shembull, në vitin 1981, Franca zgjodhi një president socialist dhe legjislaturë, gjë që dha një kryeministër socialist. Por ndërsa mandati i presidentit ishte për shtatë vjet, Asambleja Kombëtare shërbeu vetëm për pesë vjet. Kur, në zgjedhjet legjislative të vitit 1986, populli francez zgjodhi një asamble të qendrës së djathtë, presidenti socialist François Mitterrand u detyrua të bashkëjetonte me kryeministrin e krahut të djathtë Zhak Shirak.[20]

Megjithatë, në vitin 2000, ndryshimet në kushtetutën franceze reduktuan kohëzgjatjen e mandatit të presidentit francez në pesë vjet. Kjo ka ulur ndjeshëm shanset për të ndodhur bashkëjetesë, pasi zgjedhjet parlamentare dhe presidenciale tani mund të zhvillohen brenda një periudhe më të shkurtër nga njëra-tjetra.

Avantazhet dhe disavantazhet

RedaktoPërfshirja e elementeve si nga republikat presidenciale ashtu edhe ato parlamentare mund të sjellë disa elementë të favorshëm; megjithatë, ajo krijon gjithashtu disavantazhe, shpesh të lidhura me konfuzionin e krijuar nga modelet e përziera të autoriteteve. [21][22]

Avantazhet

- Parlamenti ka aftësinë të largojë një kryeministër jopopullor, duke ruajtur kështu stabilitetin gjatë gjithë mandatit të caktuar të presidentit.

- Në shumicën e sistemeve gjysmë-presidenciale, segmente të rëndësishme të burokracisë i hiqen presidentit, duke krijuar kontrolle dhe ekuilibra shtesë ku drejtimi i qeverisë së përditshme dhe çështjet e saj janë të ndara nga kreu i shtetit, dhe si të tilla, çështjet priren të shikohen sipas meritave të tyre, me zbaticat dhe rrjedhat e tyre dhe jo domosdoshmërisht të lidhura me atë se kush është kreu i shtetit.

- Të kesh një kryetar të veçantë qeverie, i cili duhet të marrë besimin e parlamentit, shihet si më shumë në harmoni me zhvillimin politik dhe ekonomik të vendit. Për shkak se kreu i qeverisë zgjidhet nga parlamenti, ka pak potencial që të ndodhë ngërç politik, pasi parlamenti ka fuqinë të largojë kreun e qeverisë nëse është e nevojshme.

Disavantazhet

- Sistemi ofron mbulesë për presidentin, pasi politikat jopopullore mund t'i fajësohen kryeministrit, i cili drejton operacionet e përditshme të qeverisë.

- Ajo krijon një ndjenjë konfuzioni ndaj llogaridhënies, pasi nuk ka një kuptim relativisht të qartë se kush është përgjegjës për sukseset dhe dështimet e politikave.

- Krijon konfuzion dhe joefikasitet në procesin legjislativ, pasi kapaciteti i votëbesimit bën që kryeministri t'i përgjigjet parlamentit.

Republikat me sistem qeverisjeje gjysmë-presidenciale

RedaktoShkrimet kursive tregojnë shtetet me njohje të kufizuar.

Sistemet kryeministrore

RedaktoPresidenti ka autoritetin të zgjedhë kryeministrin dhe kabinetin, por vetëm parlamenti mund t'i largojë ata nga detyra me një votë mosbesimi . Megjithatë, edhe pse presidenti nuk ka fuqinë për të shkarkuar drejtpërdrejt kryeministrin ose kabinetin, ata mund të shpërndajnë parlamentin.

Sistemet president-parlamentare

RedaktoPresidenti zgjedh kryeministrin pa votëbesim nga parlamenti. Për të hequr një kryeministër, ose të gjithë kabinetin, nga pushteti, presidenti ose mund t'i shkarkojë ata, ose parlamenti mund t'i largojë me një votë mosbesimi. Presidenti ka gjithashtu autoritetin për të shpërndarë parlamentin.

- Azerbaijan

- Bangladesh

- Republic of the Congo

- East Timor

- Guinea-Bissau

- Kazakhstan

- Mauritania

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- Palestine

- Russia

- Republika e Kinës (Taiwan) (Nominalisht një republikë parlamentare; sistemi gjysmë-presidencial bazohet në nene të përkohshme shtesë)[a]

Ish republikat gjysmë presidenciale

Redakto- Armenia (1991–1998, 2013–2018)[23]

- Croatia (1990–2000)

- Cuba (1940–1976)

- Finland (1919–2000)

- Georgia (2004–2018)

- Germany (1919–1933)[24]

- Greece (1973–1974)[25]

- Kenya (2007–2013)[b]

- Kyrgyzstan (1993–2021)[26]

- Mali (1991-2023)

- Moldova (1990–2001)

- Pakistan (1985–1997, 2003-2010)

- Philippines (1978–1986)[27]

- Russian SFSR (1991)[28]

- Soviet Union (1990–1991)[29]

- South Korea (1972–1988)[30]

- Tunisia (2014–2022)

- Ukraine (1991–1995)[31]

Shiko më shumë

RedaktoReferime

RedaktoReferime

Redakto- ^ The Constitution of the Republic of China specified that the National Assembly indirectly elected the President of the Republic, which is the ceremonial figurehead of the state. Executive power rested with the President of the Executive Yuan, who is nominated and appointed by the president, with the consent of the Legislative Yuan. The additional articles made the President directly elected by the citizens of the free area and replaced Legislative Yuan confirmation for Premieral appointments with a conventional vote of no confidence, superseding the ordinary constitutional provisions. A sunset clause in the additional articles will terminate them in the event of a hypothetical resumption of ROC rule in Mainland China.

- ^ Parliamentary Republic with an executive presidency and a separate Prime Minister (i.e. Votes of no confidence entailed the removal of the President).

Citations

Redakto- ^ Duverger (1980). "A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 8 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00569.x.

The concept of a semi-presidential form of government, as used here, is defined only by the content of the constitution. A political regime is considered as semi-presidential if the constitution which established it, combines three elements: (1) the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage, (2) he possesses quite considerable powers; (3) he has opposite him, however, a prime minister and ministers who possess executive and governmental power and can stay in office only if the parliament does not show its opposition to them.

- ^ Veser, Ernst [in gjermanisht] (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences (në anglisht). 11 (1): 39–60. Arkivuar nga origjinali (PDF) më 8 shkurt 2017. Marrë më 21 gusht 2016.

- ^ Bahro, Horst; Bayerlein, Bernhard H.; Veser, Ernst [in gjermanisht] (tetor 1998). "Duverger's concept: Semi-presidential government revisited". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 34 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00405.

The conventional analysis of government in democratic countries by political science and constitutional law starts from the traditional types of presidentialism and parliamentarism. There is, however, a general consensus that governments in the various countries work quite differently. This is why some authors have inserted distinctive features into their analytical approaches, at the same time maintaining the general dichotomy. Maurice Duverger, trying to explain the French Fifth Republic, found that this dichotomy was not adequate for this purpose. He therefore resorted to the concept of 'semi-presidential government': The characteristics of the concept are (Duverger 1974: 122, 1978: 28, 1980: 166):

1. the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage,

2. he possesses quite considerable powers and

3. he has opposite him a prime minister who possesses executive and governmental powers and can stay in office only if parliament does not express its opposition to him. - ^ Le Monde, 8 January 1959.

- ^ Duverger, Maurice (1978). Échec au roi (në anglisht). Paris: A. Michel. ISBN 9782226005809.

- ^ Duverger (1980). "A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 8 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00569.x.

The concept of a semi-presidential form of government, as used here, is defined only by the content of the constitution. A political regime is considered as semi-presidential if the constitution which established it, combines three elements: (1) the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage, (2) he possesses quite considerable powers; (3) he has opposite him, however, a prime minister and ministers who possess executive and governmental power and can stay in office only if the parliament does not show its opposition to them.

- ^ Veser, Ernst [in gjermanisht] (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences (në anglisht). 11 (1): 39–60. Arkivuar nga origjinali (PDF) më 8 shkurt 2017. Marrë më 21 gusht 2016.

- ^ Bahro, Horst; Bayerlein, Bernhard H.; Veser, Ernst [in gjermanisht] (tetor 1998). "Duverger's concept: Semi-presidential government revisited". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 34 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00405.

The conventional analysis of government in democratic countries by political science and constitutional law starts from the traditional types of presidentialism and parliamentarism. There is, however, a general consensus that governments in the various countries work quite differently. This is why some authors have inserted distinctive features into their analytical approaches, at the same time maintaining the general dichotomy. Maurice Duverger, trying to explain the French Fifth Republic, found that this dichotomy was not adequate for this purpose. He therefore resorted to the concept of 'semi-presidential government': The characteristics of the concept are (Duverger 1974: 122, 1978: 28, 1980: 166):

1. the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage,

2. he possesses quite considerable powers and

3. he has opposite him a prime minister who possesses executive and governmental powers and can stay in office only if parliament does not express its opposition to him. - ^ a b Elgie, Robert (2 janar 2013). "Presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Semi-Presidentialism: Bringing Parties Back In" (PDF). Government and Opposition (në anglisht). 46 (3): 392–409. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01345.x.

- ^ a b c Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries" (PDF). APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper (në anglisht). SSRN 1644026. Marrë më 18 gusht 2017.

- ^ Beuman, Lydia M. (2016). Political Institutions in East Timor: Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation (në anglisht). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317362128. LCCN 2015036590. OCLC 983148216. Marrë më 18 gusht 2017 – nëpërmjet Google Books.

- ^ "Poland 1997 (rev. 2009)". www.constituteproject.org (në anglisht). Marrë më 9 tetor 2021.

- ^ "Poland - The World Factbook" (në anglisht). 22 shtator 2021. Marrë më 8 tetor 2021.

- ^ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (dhjetor 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics (në anglisht). 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903. Marrë më 12 tetor 2017.

- ^ Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries" (PDF). APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper (në anglisht). SSRN 1644026. Marrë më 18 gusht 2017.

- ^ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (dhjetor 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics (në anglisht). 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903. Marrë më 12 tetor 2017.

- ^ Poulard JV (verë 1990). "The French Double Executive and the Experience of Cohabitation" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly (quarterly) (në anglisht). 105 (2): 243–267. doi:10.2307/2151025. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2151025. OCLC 4951242513. Marrë më 7 tetor 2017.

- ^ See article 5, title II, of the French Constitution of 1958. Jean Massot, Quelle place la Constitution de 1958 accorde-t-elle au Président de la République?, Constitutional Council of France website (in French).

- ^ Le Petit Larousse 2013 p. 880

- ^ Poulard JV (verë 1990). "The French Double Executive and the Experience of Cohabitation" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly (quarterly) (në anglisht). 105 (2): 243–267. doi:10.2307/2151025. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2151025. OCLC 4951242513. Marrë më 7 tetor 2017.

- ^ Barrington, Lowell (1 janar 2012). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices (në anglisht). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1111341930 – nëpërmjet Google Books.

- ^ Barrington, Lowell; Bosia, Michael J.; Bruhn, Kathleen; Giaimo, Susan; McHenry, Jr., Dean E. (2012). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices (në anglisht) (bot. 2nd). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. fq. 169–170. ISBN 9781111341930. LCCN 2011942386. Marrë më 9 shtator 2017 – nëpërmjet Google Books.

- ^ One-party parliamentary republic as a Soviet member-state in 1990-1991, and after independence it was a semi-presidential republic in 1991-1998, a presidential republic in 1998-2013, a semi-presidential republic in 2013-2018 and has been a parliamentary republic since 2018.

- ^ Known as the Weimar Republic.

- ^ The Greek Constitution of 1973, enacted in the waning days of the Greek Junta, provided for a powerful directly-elected president and for a government dependent on Parliamentary confidence. Neither of these provisions were implemented, as the regime collapsed eight month's after the Constitution's promulgation.

- ^ One-party parliamentary republic as a Soviet member-state in 1936-1990, a presidential republic in 1990-1993, a semi-presidential republic in 1993-2010 and a de facto semi-presidential republic; de jure a parliamentary republic in 2010-2021.

- ^ Known as the Fourth Philippine Republic.

- ^ One-party parliamentary republic as a Soviet member-state in 1918-1991 and semi-presidential republic in 1991

- ^ A parliamentary system in which the leader of the state-sponsored party was supreme in 1918-1990 and a semi-presidential republic in 1990-1991.

- ^ All South Korean constitutions since 1963 provided for a strong executive Presidency; in addition, the formally-authoritarian Yushin Constitution of the Fourth Republic established a presidential power to dissolve the National Assembly, nominally counterbalanced by a binding vote of no confidence. Both of these provisions were retained during the Fifth Republic but repealed upon the transition to democracy and the establishment of the Sixth Republic

- ^ An interim constitution passed in 1995 removed the President's ability to dissolve the Verkhovna Rada and the Rada's ability to dismiss the government by a vote of no confidence. Both of these provisions were restored upon the passage of a permanent constitution in 1996.

Referime

Redakto- Bahro, Horst; Bayerlein, Bernhard H.; Veser, Ernst (tetor 1998). "Duverger's concept: Semi–presidential government revisited". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 34 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00405. S2CID 153349701.

- Beuman, Lydia M. (2016). Political Institutions in East Timor: Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation (në anglisht). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317362128. LCCN 2015036590 – nëpërmjet Google Books.

- Canas, Vitalino (2004). "The Semi-Presidential System" (PDF). Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (në anglisht). 64 (1): 95–124.

- Duverger, Maurice (1978). Échec au roi (në anglisht). Paris: A. Michel. ISBN 9782226005809.

- Duverger, Maurice (qershor 1980). "A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly) (në anglisht). 8 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00569.x.

- Elgie, Robert (2011). Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types And Democratic Performance. Comparative Politics. (Oxford Scholarship Online Politics), Oxford University Press ISBN 9780199585984

- Frye, Timothy (tetor 1997). "A Politics of Institutional Choice: Post-Communist Presidencies" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies (në anglisht). 30 (5): 523–552. doi:10.1177/0010414097030005001. S2CID 18049875.

- Goetz, Klaus H. (2006). Heywood, Paul; Jones, Erik; Rhodes, Martin; Sedelmeier (red.). Developments in European politics (në anglisht). Basingstoke England New York: Palgrave Macmillan. fq. 368. ISBN 9780230000414.

{{cite book}}: Parametri|work=është injoruar (Ndihmë!) - Lijphart, Arend (1992). Parliamentary versus presidential government (në anglisht). Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198780441.

- Nousiainen, Jaakko (qershor 2001). "From Semi-presidentialism to Parliamentary Government: Political and Constitutional Developments in Finland". Scandinavian Political Studies (quarterly) (në anglisht). 24 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00048. ISSN 0080-6757. OCLC 715091099.

- Passarelli, Gianluca (dhjetor 2010). "The government in two semi-presidential systems: France and Portugal in a comparative perspective" (PDF). French Politics (në anglisht). 8 (4): 402–428. doi:10.1057/fp.2010.21. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 300271555. S2CID 55204235. Arkivuar nga origjinali (PDF) më 2 tetor 2018. Marrë më 6 dhjetor 2023.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1995). "From Prime Ministerial power to core executive". përmbledhur nga Rhodes, R. A. W.; Dunleavy, Patrick (red.). Prime minister, cabinet, and core executive (në anglisht). New York: St. Martin's Press. fq. 11–37. ISBN 9780333555286.

- Roper, Steven D. (prill 2002). "Are All Semipresidential Regimes the Same? A Comparison of Premier-Presidential Regimes". Comparative Politics (në anglisht). 34 (3): 253–272. doi:10.2307/4146953. JSTOR 4146953.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1997). Comparative constitutional engineering: an inquiry into structures, incentives, and outcomes (në anglisht) (bot. 2nd). Washington Square, New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780333675090.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (mars–prill 2003). "Timor-Leste: Divided Leadership in a Semi-Presidential System". Asian Survey (bimonthly) (në anglisht). 43 (2): 231–252. doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.2.231. ISSN 0004-4687. OCLC 905451085. Arkivuar nga origjinali më 14 prill 2021. Marrë më 6 dhjetor 2023.

- Shugart, Matthew Søberg (shtator 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies (në anglisht). United States: University of California, San Diego. Arkivuar nga origjinali (PDF) më 19 gusht 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Burimi journal ka nevojë për|journal=(Ndihmë!) - Shugart, Matthew Søberg (dhjetor 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics (në anglisht). 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903.

- Shugart, Matthew Søberg; Carey, John M. (1992). Presidents and assemblies: constitutional design and electoral dynamics (në anglisht). Cambridge England New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521429900.

- Veser, Ernst (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences (në anglisht). 11 (1): 39–60. Arkivuar nga origjinali (PDF) më 8 shkurt 2017. Marrë më 6 dhjetor 2023.

Linqe të jashtme

Redakto- Governing Systems and Executive-Legislative Relations. (Presidential, Parliamentary and Hybrid Systems), United Nations Development Programme (n.d.). Arkivuar 10 shkurt 2010 tek Wayback Machine

- J. Kristiadi (22 prill 2008). "Indonesia Outlook 2007: Toward strong, democratic governance". The Jakarta Post (në anglisht). PT Bina Media Tenggara. Arkivuar nga origjinali më 21 prill 2008.

- The Semi-Presidential One, blog of Robert Elgie

- Presidential Power Arkivuar 13 maj 2020 tek Wayback Machine blog with posts written by several political scientists, including Robert Elgie.